Rules to Better Code Commenting - 7 Rules

Learn effective strategies for code commenting to enhance readability and maintainability. This guide covers best practices for commenting on code updates, handling debug statements, and documenting methods and properties.

There is almost always a better alternative to adding comments to your code.

What are the downsides of comments? What are the alternatives? What are bad and good types of comments?

There is almost always a better alternative to adding comments to your code. Chapter 4: Comments, Clean Code is a treatise par excellence on the topic.

What are the downsides of comments?

- Comments don't participate in refactoring and therefore get out of date surprisingly quickly.

- Comments are dismissed by the compiler (except in weird languages like java) and therefore don't participate in the design.

- Unless strategically added, they place a burden on the reader of the code (they now have to understand 2 things: the code and your comments).

What are the alternatives to comments?

- Change name of the element (class, function, parameter, variable, test etc.) to a longer more apt name to further document it

- For ‘cryptic’ code (perhaps to optimize it), rewrite it in simpler terms (leave optimization to the runtimes)

- Add targeted unit tests to document a piece of code

-

Innovative techniques that are well known solutions to common code smells e.g.:

- For large methods/classes, break them and have longer names for them

- For a method with large number of parameters, wrap them all up in a Parameter Object

- Pair up with someone else, think... be creative

What are some bad comments?

- Those that explain the "what"/"how" of the code. Basically the code rewritten in your mother tongue

- Those that documentation comments in non-public surface area

- Commenting out the code itself (perhaps to work on it later? That’s what source control is for)

- TODO comments (Little ones are OK, don't leave them there for too long. The big effort TODOs - say that are over an hour or two - should have a work item URL to it) And many more...

What are some good comments?

- Comments that explain the why (e.g. strategic insights)

- ...that hyperlink to an external source where you got the idea/piece of code

- ...that hyperlink to a Bug/PBI for adding some context

- ...that are documentation comments for your next-biggest-thing-on-Nuget library

- ...that are real apologies (perhaps you had to add some gut-wrenching nasty code just to meeting time constraints, must be accompanied by a link to Bug/PBI)

Last but not the least, some parting words from @UncleBob himself:

"A comment is an apology for not choosing a more clear name, or a more reasonable set of parameters, or for the failure to use explanatory variables and explanatory functions. Apologies for making the code unmaintainable, apologies for not using well-known algorithms, apologies for writing 'clever' code, apologies for not having a good version control system, apologies for not having finished the job of writing the code, or for leaving vulnerabilities or flaws in the code, apologies for hand-optimizing C code in ugly ways."

* Uncle Bob (Robert Martin of 'Clean Code' fame)

Sometimes, you need to write code that deviates from the standard pattern. It might be a workaround for a library bug, an optimization for a critical performance path, or a temporary solution pending a larger refactor. Without context, a future developer, or even you, months later, might see this "weird" code and refactor it back to the standard pattern, unknowingly reintroducing a bug.

To prevent this, it's crucial to leave a clear, permanent note directly in the code. This ensures the "why" behind the decision is never lost.

The Problem with Temporary Comments

Developer comments are often temporary. We use them as personal reminders to fix something before a pull request is merged. These are often unstructured and can be confusing if left in the codebase permanently.

// GB: We need to drop database each run in DEBUG mode for local testing var db = sqlServer .AddDatabase("clean-architecture") .WithDropDatabaseCommand();Bad Example - This format is ambiguous. Is it a permanent note or a temporary reminder for the author to fix later?

The Problem with External Documentation

Another common approach is to document these decisions in a wiki, like Confluence. While great for detailed documentation, it has a major flaw.

Wiki Page: "Local Development & Testing Setup"

...To ensure idempotent and reliable local test runs, the database for the 'clean-architecture' project must be dropped and recreated on each execution when running in

DEBUGmode. This prevents data contamination between test sessions...Bad Example - Documentation is disconnected from the code. A developer won't see this unless they know to look for it, making it easy to miss.

The Solution: A Standardized NOTE Format

To solve this, use a standardized, prefixed format for these permanent notes. This makes them easy to identify, read, and search for across the entire codebase.

The format is:

// NOTE: [{{ DATE }}] {{ INITIALS }} - {{ REASON }}

// {{ OPTIONAL: see URL }}This approach provides the best of both worlds: the explanation is right next to the code, but it can also link out to more detailed documentation if needed.

// NOTE: [10 Sep 2025] GB - We need to drop database each run in DEBUG mode for local testing // see [https://github.com/SSWConsulting/SSW.CleanArchitecture/issues/421](https://github.com/SSWConsulting/SSW.CleanArchitecture/issues/421) var db = sqlServer .AddDatabase("clean-architecture") .WithDropDatabaseCommand();Good Example - The

NOTE:prefix makes the intent clear. The comment is permanent, explains the deviation, and provides a link for more context.This standardized format ensures:

✅ Clarity: It's immediately obvious that this is a permanent and important note.

✅ Discoverability: The reason for the non-standard code is impossible to miss.

✅ Consistency: The format is easy to recognize and search for codebase-wide.

✅ Traceability: It provides a clear link between the code and the business/technical requirement in the work item or documentation.When you create comments in your code, it is better to document why you've done something a certain way than to document how you did it. The code itself should tell the reader what is happening, there's no need to create "how" comments that merely restate the obvious unless you're using some technique that won't be apparent to most readers.

What do you do with your print statements? Sometimes a programmer will place print statements at critical points in the program to print out debug statements for either bug hunting or testing. After the testing is successful, often the print statements are removed from the code. This is a bad thing to do.

Debugging print statements are paths that show where the programmer has been. They should be commented out, but the statements should be left in the code in the form of comments. Thus, if the code breaks down later, the programmers (who might not remember or even know the program to start with), will be able to see where testing has been done and where the fault is likely to be - i.e., elsewhere.

private void Command0_Click() { rst.Open("SELECT * FROM Emp") // Open recordset with employee records // Debug.Print("Got " + intCount + " results"); if (intCount > 1000) { // Debug.Print("too many records - returning early"); return; } else { .....processing code }Bad example - Debug code has just been commented out

private void Command0_Click() { rst.Open("SELECT * FROM Emp") // Count will exceed 1,000 during eighteenth century // leap years, which we aren't prepared to handle. if (intCount > 1000) { return } else { .....processing code }Good example - The debug commands have been rafactored into meaningful comments for the next developer

It's important that you have consistent commenting for your code, which can be used by other developers to quickly determine the workings of the application. The comments should always represent the rationale of the current behaviour.

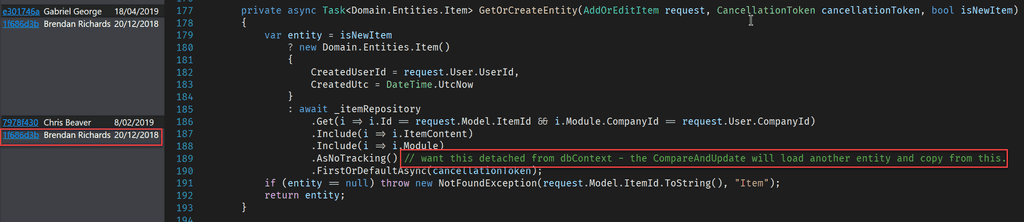

Since applications evolve over time - don't add comments to your code with datetime stamps. If a developer needs to see why the code behaves the way it does right now - your commit history is the best place to tell the story of why the code has evolved.

Commands such as git blame or Visual Studio's annotate are great ways of seeing who and when a line of code was changed.

private void iStopwatchOptionsForm_Resizing(object sender, System.EventArgs e) { // Don't close this form except closing this application - using hide instead; if (!this.m_isForceClose) { // <added by FW, 11/10/2006> // Remind saving the changes if the options were modified. if (this.IsOptionsModified) { if (MessageBox.Show("Do you want to save the changes?", Me.GetApplicationTitle, MessageBoxButtons.YesNo, MessageBoxIcon.Warning) = DialogResult.Yes) { this.SaveOptions() } } // </added> } }Figure: Bad example - Timestamped comments add noise to the code

It's common to add a

TODOcomment to some code you're working on, either because there's more work to be done here or because you've spotted a problem that will need to be fixed later. But how do you ensure these are tracked and followed up?We add a

TODOcomment to our code when we have either identified or introduced technical debt as a way of showing other developers that there's work to be done here. It could be finishing the implementation of a feature, or it could be fixing a bug which (hypothetically) is limited in scope and therefore deprioritized. That's all well and good if another developer happens to be looking at that code and sees the comment, but if nobody looks at the code, then the problem could potentially never be fixed.public class UserService(ApplicationDbContext context) : IUserService { public async Task<UserDto> GetUserByEmailAsync(string emailAddress, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default) { var dbUser = await context.Users .AsNoTracking() .FirstOrDefaultAsync(u => u.Email == emailAddress, cancellationToken); // TODO: handle null user if not found return new UserDto { Id = dbUser.Id, Name = dbUser.Name, Email = dbUser.Email, TenantId = dbUser.TenantId.ToString() } } }Bad example - There is problematic code here, and while the comment is useful as it immediately alerts developers to the problem, but it is not tracked anywhere

Just like with any other technical debt, it's critical to ensure that it is captured on the backlog. When you add a

TODOin your code, it should always be accompanied by a link to the PBI.public class UserService(ApplicationDbContext context) : IUserService { public async Task<UserDto> GetUserByEmailAsync(string emailAddress, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default) { var dbUser = await context.Users .AsNoTracking() .FirstOrDefaultAsync(u => u.Email == emailAddress, cancellationToken); // TODO: handle null user if not found. // https://github.com/Northwind/Northwind.UserManagement/issues/324 return new UserDto { Id = dbUser.Id, Name = dbUser.Name, Email = dbUser.Email, TenantId = dbUser.TenantId.ToString() } } }Good example - The

TODOis tracked on the backlog, so the developers and the Product Owner have visibility of the problem and can plan and prioritise accordinglyTip: If you are reviewing a Pull Request and you spot a

TODOwithout a link to a PBI, you should either create the PBI and update the code (Good Samaritan) or request the change before approving and merging the code.First don’t do it and find the right fix. But if you have to, it should always be commented – as though your life depended on it.

public DialogResult RefreshSchema() { SSW.SQLAuditor.WindowsUI.QueryAnalysisForm.RunScript(Startup.PageQueryAnalyzer.txtScript.Text) System.Windows.Forms.Application.DoEvents() // This is a sleep to delay the Application.DoEvent process. System.Threading.Thread.Sleep(500) System.Windows.Forms.Application.DoEvents() ... }If you have to use a workaround you should always comment your code.

In your code add comments with:

- The pain - In the code add a URL to the existing resource you are following e.g. a blog post

- The potential solution - Search for a suggestion on the product website. If there isn't one, create a suggestion to the product team that points to the resource. e.g. on https://uservoice.com/ or https://bettersoftwaresuggestions.com/

"This is a workaround as per the suggestion [URL]"

Figure: Always add a URL to the suggestion that you are compensating for

Exercise: Understand commenting

You have just added a grid that auto updates, but you need to disable all the timers when you click the edit button. You have found an article on Code Project (http://www.codeproject.com/Articles/39194/Disable-a-timer-at-every-level-of-your-ASP-NET-con.aspx) and you have added the work around.

Now what do you do?

protected override void OnPreLoad(EventArgs e) { //Fix for pages that allow edit in grids this.Controls.ForEach(c => { if (c is System.Web.UI.Timer) { c.Enabled = false; } }); base.OnPreLoad(e); }Figure: Work around code in the Page Render looks good. The code is done, something is missing