Do you know what “exploratory testing” is?

Last updated by Lee Hawkins [SSW] about 3 years ago.See historyExploratory testing is an approach to testing that fits very well into agile teams and maximises the time the tester spends interacting with the software in search of problems that threaten the value of the software.

Exploratory testing is often confused with random ad hoc approaches, but it has structure and is a credible and efficient way to approach testing.

Let's dig deeper, look into why this approach is so important, and dispel some of the myths around this testing approach.

Definition

James Bach and Michael Bolton define Exploratory Testing (ET) as follows:

Testing is the process of evaluating a product by learning about it through exploration and experimentation, which includes: questioning, study, modeling, observation and inference, output checking, etc.

Other definitions of exploratory testing focus on the idea of learning, test design and test execution being concurrent (rather than sequential) activities. Exploratory Testing is an approach to software testing that emphasizes the personal freedom and responsibility of each tester to continually optimize the value of their work.

Why is exploratory testing so important?

Exploratory testing affords testers the opportunity to use their skills and experience to unearth deeper problems in the software under test.

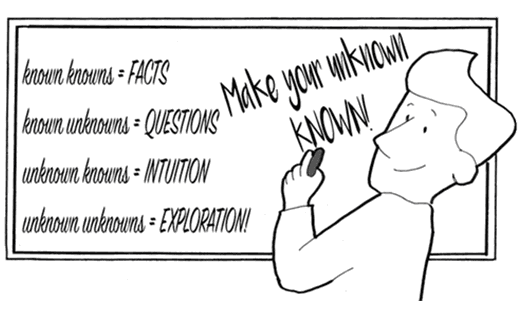

Rather than constraining the testing to "known knowns" (from requirements, user stories, etc.), exploration allows different kinds of risks to be investigated and "unknown unknowns" to be revealed.

It is often the case that the most serious problems in the software reside in these areas that were not clearly specified or understood before testing started.

How does exploratory testing compare with scripted approaches to testing?

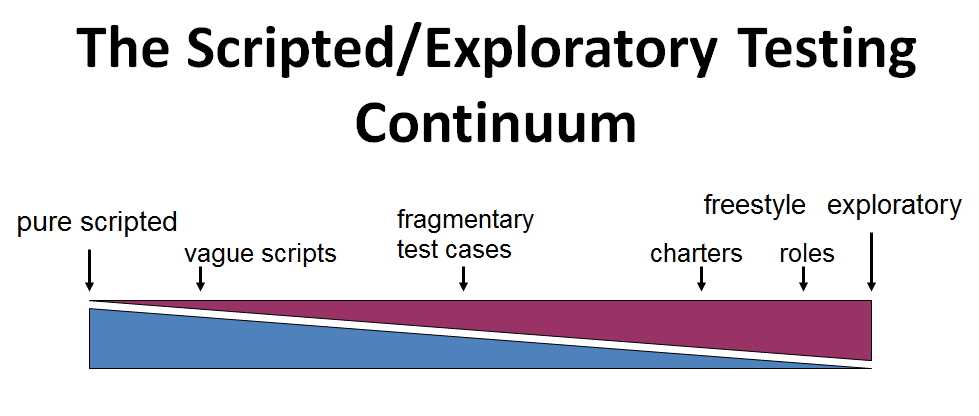

No matter how you currently perform testing within your team, your approach will belong somewhere on a continuum from a purely scripted form of testing to a fully exploratory form of testing:

A purely scripted approach is favoured by the "factory" school of testing, where scripts are created in advance based on the requirements documentation and are then executed against the software later, potentially by someone different than the author. The idea here is that everything can be known in advance and coverage is known and guaranteed via the prescriptive steps in the test case. This approach is obviously very rigid and does not account well for when unexpected things happen during execution of the script or for the fact that different testers will execute the exact same steps differently (breaking the so-called benefit of "reproducibility" in purely scripted testing).

Scripts can be made more vague, by specifying the tests in a step-by-step fashion but leaving out any detail that does not absolutely need to be specified (one way to do this is to omit the "Expected Results" for each step, thereby making the tester think more about whether what they see is what they realistically expect to see). You can then consider a more improvised approach in which you still have scripts, but actively encourage deviation from them.

A middle ground is fragmentary test cases, where you specify tests as single sentences or phrases, eliminating the step-by-step detail and omitting prescriptive expected results. Charters are a key concept in managing exploratory testing and they basically specify a mission for a timeboxed period of testing (say, 90 minutes), with the mission being expressed in two sentences or less - enough direction to focus the tester on their mission, but leaving enough freedom for the tester to exercise their judgment and skill.

Another exploratory approach is to assign each tester a role to test a certain part of the product, then leave the rest up to them. The use of heuristics becomes more critical and valuable as you approach this exploratory end of the continuum, to help the tester come up with test ideas during their freestyle exploratory testing.

Some exploratory testing myths

Exploratory Testing is just a fancy name for ad hoc testing

Random "keyboard bashing" and testing without any real direction or purpose is ad hoc testing, it is not exploratory testing. Remember that in true exploratory testing, the tester is learning, designing and executing tests concurrently - they are not just randomly doing things without thinking about what they are doing, what particular kind of issues they are looking for, and what test ideas they need to use to look for those kind of issues. In fact, ET is systematic, not random.

Exploratory Testing is too unstructured to be taken seriously

The structure of ET comes from many sources:

- Test design heuristics

- Chartering

- Timeboxing

- Perceived product risks

- The nature of specific tests

- The structure of the product being tested

- The process of learning the product

- Development activities

- Constraints and resources afforded by the project

- The skills, talents and interests of the tester

- The overall mission of testing

One structure, however, tends to dominate all the others - the Testing Story. Exploratory testers construct a compelling story of their testing and it is this story that gives ET a backbone. To test is to compose, edit, narrate and justify three stories:

-

A story about the status of the product

- About how it failed and how it might fail

- In ways that matter to your various clients

-

A story about how you tested it

- How you configured, operated and observed it

- About what you haven't tested, yet

- And won't test, at all

-

A story about how good that testing was

- What the risks and costs of testing are

- How testable (or not) the product is

- What you need and what you recommend

The testing story can be recorded in artifacts called session sheets but it should be obvious that the richness of this storytelling provides stakeholders with much more valuable information about your testing than, say, a pass/fail result on a test case.

Exploratory Testing doesn't work unless you have highly experienced testers

It is a misconception that an exploratory approach to testing is best reserved for highly experienced testers. Less experienced (even less skilled) testers can still become great exploratory testers if their mindset is right for it - a desire to continually improve and learn is required, as is a genuine interest in providing value to their projects by providing testing-related information in a way that stakeholders can act upon.

Exploratory Testing lacks the rigour to be used in regulated environments

The different approach to documenting the test effort in exploratory testing is often claimed to lack the rigour required by auditors for teams working in regulated environments, such as finance or healthcare. This is simply untrue and there are now many well-documented case studies of the use of ET within regulated industries. Auditors are generally interested in answering two questions: "can you show me what you're supposed to do?" and "can you show me the evidence of what you actually do?". They are less interested in the form that the evidence takes. For example, formal test scripts actually provide less evidence of what was actually tested than a well-written testing story from a session of exploratory testing.

Josh Gibbs has written on this topic in his article Exploratory Testing in a Regulated Environment and James Christie is another excellent advocate for the use of ET within regulated environments, as he spent many years as an auditor himself and knows the kinds of evidence they seek in order to complete their audits. Griffin Jones gave an excellent presentation on this topic at the CAST 2013 conference, What is Good Evidence.

Further reading

- James Bach & Michael Bolton - History of Definitions of ET

- James Bach & Michael Bolton - Exploratory Testing 3.0

- Ministry of Testing - Exploratory Testing resources